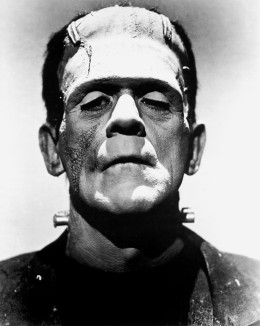

One of the most canonical gothic (and romantic) novel, Frankenstein by Mary Shelley has become, over the decades, a pop icon. It is now sadly best known as a horror movie’s character and a freak of nature that captures popular imagination and haunts modern fictions. At the beginning of 2014, an umpteenth adaptation of the novel (more exactly of a comic book derived from it) in the form of a thriller (a futuristic dystopia), « I, Frankenstein », was released, and panned by critics. The director Guillermo del Toro, also plans a more faithful adaptation reflecting « a Miltonian tragedy » he said. The work also introduced the now famous figure of the « mad scientist » overpowered by its terrible and out-of-control creation.

Yet, beyond this powerful cinematic and cultural imagery, loosely based on the 1818 novel, the original text and its psychological and philosophical facets tend to be forgotten, in favor of a more sensational or extreme representation.

First common misuse about this (ill-fated) anti-hero : Frankenstein is not the creature’s name (who remains -on purpose- nameless) but that of the unfortunate creator.

A symptomatic confusion which denotes one of the novel’s key interpretations consisting of viewing the two of them as the two sides of the same coin.

To situate « Frankenstein » within literary – and more particularly gothic novel- history, it was published at the beginning of the 19th century, when the British romantic movement was coming of age. As for the gothic novel, considered a -somewhat debased- subgenre of Romanticism, it started to enjoy its own golden age too at this period.

Inspired by Shakespearian drama (such as Macbeth) and initiated in 1763 with « The Castle of Otranto » by Horace Walpole who laid its foundations, it gained momentum with « The mystery of Udolpho » by Ann Radcliffe in 1794 (often cited as the archetypal Gothic novel), both introducing the figure of the « gothic villain ». « The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mister Hyde » by Tevenson (with « Frankensteinian » undertones) would only come out in 1885 and Dracula by Bramstoker in 1897.

But, is Mary Shelley an heir of these authors? Yes… and no. We’ll go into more detail about this aspect in the course of the article.

Of course, she draws upon some gothic staples (oft fainting heroine, « damsel in distress », etc.) but at the same time she breaks away from them with some new features (male heroes and their duality/inner struggle) and mostly a new figure of the gothic vilain. Some even go as further as to claim the novel as a science fiction precursor.

Whatever it be, the story, originally written, as the legend goes, as a friendly writing competition among Mary, her husband Percy Shelley and Lord Byron among others, gave rise to a multitude of interpretations from biblical, mythological, political approach through to feminist or autobiographic. The author, herself, more or less overtly, drew upon great myths and Scriptures.

Firstly her subtitle refers directly to Prometheus who, in Greek mythology, is a Titan who defies the gods and steals fire (which stands for knowledge) to offer it to mankind.

This cautionary -and allegorical- tale can be looked at through various lenses revolving around existential themes including human ambition -and especially the thirst for boundless knowledge- but also the irrepressible -and desperate- need for -all kinds of- love, and finally simply the eternal pursuit of happiness often ruined by our inner struggles and human passions ranging from fear, revenge and hatred.

I/The Primal Needs for Love and for Learning: Two tenets of the Basic Human Instincts

What are the central theme and message of the novel ? It is commonly summed up as a story about a (reputed) evil quest of (God-like) knowledge leading to the fall of the hapless main character and his beloved ones along with the danger of « crossing the -allowed- line ».

However this reading could sound somewhat reductive. If we scratch beneath its surface and think it over, we may find something more complex that actually connects two powerful primal human instincts : the pursuit of knowledge (in other words « understanding ») associated with creation on one hand and that of love on the other hand.

Frankenstein is a story deeply rooted in human instincts and fundamental emotional needs and hardwired responses which explores how they are interelated and how they impact one another (lack of love and rejection trigger hatred and prompt the urge for revenge, how obsession leads to self-destruction, or how being fearless endowes with power, etc.).

Shelley crafts with brio a series of catalysts acting like (catastrophic) chain reactions.

Yet, one will notice the jarring absence of sex or lust in her depiction, and instead the craving for affection…

Shelley does nothing less than delving into this fantastic playground made up of human « dark » passions, just as Shakespeare did.

It’s more particularly the juxtaposition of the learning and love quests which is interesting and prompts us to examine their relationship.

Humans are literally wired to learn. It’s an impulse (linked to curiosity) we cannot help it : we constantly need to move on, to advance, to move forward, to get ahead. Mankind cannot make do with what he has and perpetually needs to explore, discover and conquer new uncharted territories. In other words : to overstep boundaries.

It’s an enduring quest which probably only ends with human extinction !

As the author puts it in the mouth of the creature : “Of what a strange nature is knowledge! It clings to the mind, when it has once seized on it, like a lichen on the rock.”

In other words, knowledge has an addicted quality.

What’s more, Mary Shelley wrote in the immediate aftermath of The Age of Discovery (colonization of the American continent she mentions in her work), at the heart/height/peak of the Industrial and Scientific Revolution’s creative bustling/period turmoil, when the Industrial Revolution was reaching its peak. She was more specially influenced by Galvanism (which was supposedly able to re-animate dead tissue).

Her unfortunate Frankenstein mirrors perfectly this passionate spirit eager for discoveries and technological breakthroughs.

And this, in the wake of Doctor Faustus by Christopher Marlowe (1604), was definitely wrong in Shelley’s point of view as she conveys the idea that this thirst for « forbidden » knowledge is destructive. Therefore this harmful impulse must be repressed, as she puts it between the lines… or quite clearly at times :

« How dangerous is the acquirement of knowledge and how much happier that man is who believes his native town to be the world, than he who aspires to be greater than his nature will allow. »

However, some other readings of the book consider it to be more a warning rather than an interdiction in the form of a recommendation for being responsible for what we create.

This second interpretation could be supported by the fact that Frankenstein is devoid of malevolent intentions (contrary to Faustus) and intended initially to serve his « fellow creatures »

« I had begun life with benevolent intentions and thirsted for the moment when I should put them in practice and make myself useful to my fellow beings. » (chapter 9)

Unlike Faustus his quest gets across more altruistic as the subtitle « The modern Prometheus » suggests it (Prometheus gave fire to mankind ; his thief was for a gift and not self-interest).

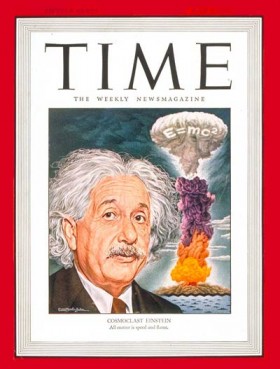

From Frankenstein to Einstein…

This idea is beautifully (and tragically) rendered in one of the most famous lines of the book, in chapter 20, when the monster visits Frankenstein and scolds him for breaking his promise to make him a wife. He then asserts terribly his power over him: “You are my creator, but I am your master — obey! »

This thesis can easily find applications in the 20th and 21th century (cf : Einstein -whose name was oddly echoed prophetically by that of Frankenstein- and the Atomic Bomb or nowadays Mark Zuckerberg and Facebook).

Thus, Shelley raises various ideological/moral issues that render the book so powerful/ underpin/constitute the power of the book : how to deal with knowledge « an unwholesome trade » associated with the « unhallowed arts », activité illicite, arts occultes > connotation religieuse de l’époque opposition to The Enlightment > gothic ideology ? Is knowledge really dangerous or ? Do human beings have the right to pursue science over ideology ?

Shelley doesn’t solve these questions only by dismissing and condemning the idea of progress altogether.

Ambition vs Over-achiever vs. Overreacher

This quest for an unfettered knowledge and the pushing of limits, associated with God’s pretentions refers to various notions ranging from ambition, over-achiever and overreacher

It’s interesting to compare these various traits that are close but imply a more or less negative moral judgement.

When looking up in a dictionnary, we can notice two different meanings for « ambition ». A more neutral one which refers to a strong desire/will to achieve something and a second one that relates more to wealth, rank, fame, or power which contains disapproval overtones.

An overreacher is a literary term that cannot be found in the dictionnary. It derives from the verb « overreach » which means « try to do more than your ability, authority, or money will allow« . An overreacher is defined as a person who wants to go beyond the human limits challenging god’s power.

It contains this notion of « overstepping » and as a by-product that of disobedience (doing what is not « allowed »). This notion is very questionable as it totally leaves out the risk-taking factor and therefore makes progress impossible…

Indeed taking risks is part of the advancement process, it involves pushing ourselves out of our comfort zones in order to gain new experiences and perspectives.

All of human history and civilization are based on this principle and denying it results in refusing progress.

The overreacher stock character would date back to Marlowe. He refers to a certain type of « classical tragic hero in the works of Sophocles » and relates to the Greek word “hyperbole”. « Marlowe characters have an exaggerated appetite for achievement, whether it’s world conquest (Tamburlaine), knowledge as power (Faustus) or revenge and the acquisition of riches (Barabus). » They are considered « fascinating portraits of English imperial ambitions. »

Finally, an over-achiever (it’s worth noting that this term doesn’t exist in French for instance) is a quite recent term as its first use is recorded as being in 1952. The definition reads « someone who tries extremely hard to be successful and puts pressure on themselves to achieve many things » Another definition states « one who achieves success over and above the standard or expected level especially at an early age. »

Slightly more positive, this « label » can still sound like a reproach according to the context.

So the question could be who is really Frankenstein, an ambitious, an overachiever or an over-reacher (as he is often considered to be the epitome) ?

To Mary Shelley, the answer is definitely the last one but on the other hand we could also admire, his dedication, his commitment, his intelligence and his hard work even though the end result was not what he expected…

Victor felt he was « destined for some grand enterprise »and « great design ». There is nobility in his initial move.

Rather than outstepping, couldn’t we view him as trying to outdo himself, through the lens of self-improvement?

He also endeavours to confront his creature to stop his misdeeds although to no avail, and repents dearly and tries to redeem himself contrary to Faustus who denies God to the very end.

Frankenstein never mentions worldly goals but rather helping people. His goals hold more an altrustic quality hence the comparison with Prometheus.

Yet ambition rarely appears « worthwile » but rather a vice and a destructive obsession.

It is associated with an « ungovernable passion » likely to lead to trouble. As a result the drive to get ahead is usually (for cultural and religious reasons) reviled.

Flirting with omnipotence : Playing at being God

Frankenstein is often primarily depicted as « the story of a man’s (a scientist’s) attempt to usurp the role of God in creating life. »

Its plot is indeed filled with mythological and biblical references underpinned by the « don’t-steal-the-power-away-from-God » doctrine (the recurrent thme in stories of humankind origin) that was also a staple of Shakespeare’s plays where God was replacing by the Queen or the King. From this viewpoint, only God is the creator, and there is always a price to be paid by one surging beyond accepted human limits.

The pursuit of knowledge is originally viewed as a sin, the « original sin » where the forbidden fruit symbolizing the forbidden knowledge (« of Good and Evil ») was eaten by Adam ensuing the fall of Men and his banishment from the Garden of Eden. This classic tragic theme of failed ambition is also at the core of other great myths such as The Babel Tower or The Myth of Icarus.

Shelley refers directly to the founding biblical myth from the Book of Genesis through the masterpiece Paradise Lost by J.Milton (Lucifer is expelled from Heaven and Adam from Eden when they challenge their creators) that was found by the monster and read avidly.

The creature also calls himself, when speaking to Victor, the « Adam of your labours« .

Frankenstein’s thirst for knowledge has also been passed down to his creature who becomes eager to learn more about the world during his « cottage period ».

He relates closely to Milton’s work, comparing himself to both Adam and Satan, perceiving himself as both human and demonic. Blamed like Adam and cursed like Satan, the monster suffers from his creator’s fierce disgust.

The link between knowledge and (un)happiness

« (…) sorrow only increased with knowledge. » This quote is maybe one of the most powerful of the novel and contains its essence. It comes up in chapter 13 when the monster recounts his story to his creator, and more particularly his « vicarious education » through his little neighbour’s lessons he eavesdropped.

He learnt about the world he’s living in made up of « wealth and squalid poverty », wars, social hierarchy, the rule of money over that of the heart or human qualities, etc.

And he grew « disgusted and loathing » with this society.

He even goes as far as to state that he would have preferred « to remain forever in his native wood, nor knowing nor feeling beyond the sensations of hunger, thirst, and heat! »

This echoes exactly Frankenstein’s reflections in chapter 4, in retrospect when he envies the man who never ventures beyond his native town.

The « pursuit of happiness » as the US motto goes, and entrenched in the Declaration of Independence, comes into play and challenges that of knowledge. In Shelley’s view, the latter is clearly detrimental to the former and even prevents it, in other words they are incompatible.

She repeats this idea when Victor deems that some « unlawful » study « weakens your affections and destroys your taste for those simple pleasures« .

Learned men lose their « joie de vivre ». We can connect this image with the character of Esther’s husband, Chillingworth (from « The Scarlet Letter », 1850), a man of science who becomes a vengeful and obsessed fiend.

We can feel here, the common distrust and dislike of science by romantic writers.

There is also a biblical root to this ingrained idea that wisdom brings sorrow (The Ecclesiastes).

In the same vein, we can also think of « Martin Eden » by Jack London, whose eagerness to getting learned and create leads him to isolation and, among other causes, to suicide… A very « Frankeinsteinian » hero after all, with in addition a family name that seems to echo the fall in the Garden of Eden…

Thus, knowledge is dangerous because he plants the seeds of sadness and despair in the minds. But at the same time, knowledge is inevitable and ignorance is not a possible and fulfilling way of life either, despite the two characters utopian wishes.

Once again a philosophical question is raised here. We must be able to face and stand reality, as horrible it could be. The key to meet this challenge lies maybe simply in… love (even though it may sound quite pat and saccharine !).

Upon the monster’s request to make him a wife, Victor acknowledges that « As his maker [I] owe him all the portion of happiness that it was my poser to bestow« .

The irrepressive need for love

When love goes wrong, nothing goes right…

Love is indeed at the heart of the novel that could also have been subtitled « The monster who wanted to be loved ». Much more cheesy, right… Anyway 🙂

The novel is a romantic one so this makes sense even though the literary meaning of « romantic » differs somewhat from the modern definition, still it lays an emphasis on emotions and passions, especially the celebration of love.

Along with the absolute and compulsive need for knowledge human beings come with this primal and vital need and urge for love. Unless the famous « hierarchy of needs » by Maslow, sex is absent in this novel, something that could be discussed too (along with the fact that the scientist creates life without sexual intercourse).

Shunned and reviled by his « father-creator » and then by society, the « big-hearted creature » experiences an unbearable feeling of isolation and rejection. After his attempts to connect and bond with people prove to be total failures, it’s interesting to see how this lack of love and social acceptation/interaction turn into anger and the will of revenge. “If I cannot inspire love, I will cause fear!” he warns terribly.

There is indeed an evolution of the creature from an initial benevolent and even virtuous nature to a cruel and ruthless murderer. In this way, he was compared to the « noble savage » by Rousseau.

The lack of love seems to be the root of hatred and evil, even though it sounds like a somewhat simplistic psychological shortcut… The alternative biological response to social and emotional rejection would be death which will be the final outcome anyway.

Through his outcast condition Shelley shows cleverly a great array of feelings and emotional responses along with a social critique that comes through.

Indeed, the monster is never judged by his inner -and true- self but only by his outward appearance, his « physical uglyness » in opposition with his gentle and caring behaviour.

He is even called by the cottagers ‘good spirit,’ ‘wonderful’ when they ignored who he was.

We can point out here again a biblical influence in this theme of physical prejudice

Numerous verses refer to this human flaw : « man looks on the outward appearance, but the Lord looks on the heart.” or « Stop judging according to outward appearances; rather judge according to righteous. »

Shelley shows social hypocrisy that primarily judge by the way one looks and the inability to overcome it. « The human senses are insurmontable barriers to our union » the resigned monster observes.

This irreconciliable dichotomy between inner and outer self is also perceived when Frankenstein listens to him and then looks at him, experiencing contradictory feelings (between sympathy and revulsion) : « His words had a strange effect upon me. I compassionated him and sometimes felt a wish to console him, but when I looked upon him, when I saw the filthy mass that moved and talked, my heart sickened and my feelings were altered to those of horror and hatred. »

Besides love, the theatre of passions and more precisely intense « dark passions » take centre stage in the novel. The great Romantic works often center on terror or rage. They also draw upon fear and a form of awe, under the influence of the essay « A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful » by Edmund Burke(1757) who equated the sublime with astonishment, fear, pain, roughness, and obscurity and the beautiful with a set of opposite qualities (calmness, safety, smoothness, clarity, and the like).

It’s worth nothing that his study was also based on Milton’s Paradise Lost.

He believed that « terror was the ruling principle of the sublime, the idea of astonishment, the state of the soul, in which all motions are suspended« . Contrary to beauty which has a relaxing effect, he suggested that sublimity tightens the fibers of the body and the tension of the nerves. To him, « terror and pain were the strongest emotions and contained an inherent pleasure. »

Shelley’s monster follows these principles as he sparks terror by his « unearthly ugliness », the « greatness of his dimensions » (as Burke states it) or « the deformity of its figure ».

Both the creature « grovelling in the intensity of [his] wretchednessand » and the creator suffer « infinite pain » and a « hell of intense tortures« , described at length throughout the narrative, and are soothed, at times, by the « healing power » of nature.

Frankenstein is also deeply racked with guilt, anguish and depair : « Anguish and despair had penetrated into the core of my heart; I bore a hell within me which nothing could extinguish. »

And yet, the necessity to control one’s emotions…

But at the same time there is still a need to check/control by reason these

fevered emotionalism and exalted sentiments >> Enlightment influence. To be able not to be overwhelmed by pain.

« There is an expression of despair, and sometimes of revenge, in your countenance that makes me tremble. Dear Victor, banish these dark passions. » (Elizabeth to Victor)

We find this concern (not letting feelings/distress overcome you and deprive you of reason) in various gothic works such as The castle of Otranto where the character of Matilda embodies this necessity of keeping calm and composure and not let fear « infect her ». In The mysteries of Udolpho, agonizing Mr Saint Aubert « guards her daughter against the dangers of sensibility« , on his deathbed, and recommends her to « command » her feelings to not become their victim » while calling an ill-governed sensibility, a « vice ».

He also states that « happiness arises in a state of peace, not of tumult. »

Frankenstein follows the same path when Victor comments about knowledge seen as a corruption contributor of the mind and a troublemaker : « A human being in perfection ought always to preserve a calm and peaceful mind and never to allow passion or a transitory desire to disturb his tranquillity. »

Bringing together love and knowledge :

How to deal with and « domesticate » knowledge without being harmed or « wretched » ?

Although Shelley didn’t suggest this « third way », a possible coda of her story seems to lie in « love », in the broad sense that is to say a more caring/human/ethical approach of science and knowledge (moral standards) could allow scientific progress without detrimental effects.

And not just a ruthless and heartless, self-interested search for technical performance and prowess.

Shelley advocates rather the utopic confinement of men within « permitted » bounds and ends her novel on a dramatic and pessimistic warning note.

But maybe without her knowledge (pun not intended), she indirectly suggests this option that suits better the modern evolution of science and the advent of genetic engineering with the introduction of bioethics for instance.

Copyright : Buzz… littéraire, please don’t plagiarize this work for academic papers but rather use citations.

Please feel free to report any mistake you may notice (ESL work). Thank you in advance.

Derniers commentaires