The Victorian Age is considered to be the heyday of the gentlemanly ideal, both in society and in literature. Indeed, the Victorian period developed a quasi obsession with gentility and gentlemanliness. In the late 18th century, Edmund Burke already emphasized « the spirit of gentleman » and complained that « the age of chivalry [was] gone… and the glory of Europe [was] extinguished » (Reflections on the Revolution in France, 1790). The next generation of novelists in the 19th century, Thackeray, Dickens and Trollope, were also all fascinated by his image, and impressed upon society their views on gentlemanliness (Berberich). The problem of the self-made or would-be gentleman -and the contradictions of the English class system- were some of the subjects they explored.

Dickens dealt with the lower end of the middle-class, while Thackeray focused on the bourgois (Vanity Fair 1847-48, The Book of Snobs 1848).

Joe, Pip, Estalla, and Miss Havisham in « Great Expectations » by Dickens (Source: The Collector’s Library).

In Great Expectations (1860) Dickens delivered « the, perhaps, most profound and thorough commentary on the Victorians’ preoccupation with gentility » according to Gilmour (p.107). It is considered to be at once « a portrait or a definition of Dickens’s concept of the Gentleman and a justification of his own claim to that title » (Cody). His main character, the young and idealistic Philip Pirrip (Pip), is an orphan in London who yearns « to be a gentleman » and to rise from his humble roots to the upper class. In this sense he exemplifies the advent of the « nature’s gentleman« , and the new possibility of social advancement through constant striving and impeccable morals (cf. his denigration for his bad behavior and bad deeds). Pip eventually realized that inner values rather than flaunting wealth make a man a gentleman.

In Vanity Fair, Thackeray’s characters follow the same path by rejecting the traditional -aristocratic- image of a gentleman as a man of rank and leisure, and instead valuing his moral qualities of altruism, benevolence, and his culture and education. Even though he suffered from his well-born, well-bred and well-educated background, he was the first major novelist to capture the conflict between the aristocracy and the middle classes in the early Victorian decades (Gilmour).

Research Questions:

In this project I sought to investigate the definition of a gentleman, why was this figureso central in this era as reflected in literature, and how it shaped the Victorian masculine ideal, culture, gender roles, and (patriarchal) society values at large.

[ETYMOLOGY AND ORIGINS]

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, in 1929, the word is formed of the French « gentilhomme« , or rather of gentil, « fine, fashinable, or becoming; » and the Saxon man, q.d honestus, or honesto loco natus.

If we go further back, gentleman originally derivated from the Latin gentiles homo: which was used among the Romans for a race of noble persons.

The 1929 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica describes the gentleman as « in its original and strict signification, a term denoting a man of good family« , before this definition had been widened over time (see below).

First used in 1413, it originated in feudal society. Thus the medieval knight, as a just righter of wrongs following a code of moral conduct and courteous toward women can be considered the forerunner (Berberich). Originally, the gentleman was the man of noble birth with his pure gens, but also the Church of England clergymen, members of Parliament and army officers.

From its earliest usage in English, the term “gentle” carried both social and moral connotations, as did “noble”. It was always a complimentary term.

A man of gentle disposition (« gentil »), as early as Chaucer’s time, meant “charming”, « mild » and « tender », as well as “worthy”, « noble », and « well-bred ». These qualities embodied a chivalric ideal, whereby men of high rank justified their superiority by their gracious and courteous bearing.

In the 15th century, as land was the main source of status and power, the term certainly applied mainly to freehold landowners (Corfield).

By the 16th century it had become into general use as the Renaissance was an era of men’s self-fashioning. The self-fashioned man is associated with the self-made man, in the sense that he knowingly models himself according to certain behavioural rules; he builds-up a career, business or fortune from scratch. Central to this new man, manners were then required to impress at court and closely connected with gentlemanly behavior. Edmund Burke already wrote in his « First Letter on a Regicide Peace » (1796) that they were “of more importance than laws… »

They have changed considerably over time though.

While chivalry code was a product of the Middle Ages (that came under Humanist writers’ fire for their violence and licentiousness) , it was soon replaced by courtesy, civility, conduct, politeness and etiquette. Courtesy still had a connection with the medieval knight but its gradual supersession by the term « civility » in early modern writing on manners indicates a “bourgeoisification » of « codes of conduct », culminating in the elevation of manners to quasi-religious status for the Victorian middle classes.

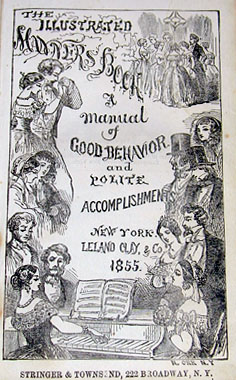

The Illustrated Manners Book; A Manual of Good Behavior and Polite Accomplishments. New York: Leland, Clay, & Co., 1855.

Based on the etiquette columns of the illustrated monthly magazine The Dime, this book of manners features many wood-engravings done by young women who were students at the New York Female School of Design, an art school for women (University of Delaware Library)

How to Behave and How to Amuse: A Handy Manual of Etiquette and Parlor Games. New York: Christian Herald, 1895.

The book includes topics such as behavior in church, dozing in public, and monopolizing conversations. It contains games and riddles, magic tricks, and hypnotism. There is much emphasis on the wholesomeness of these activities as opposed to dancing and other questionable pastimes (University of Delaware Library).

Both courtesy books – most popular in the 17th and 18th century- and 19th etiquette books – targeting a new middle-class audience- were written with the aim of self-fashioning. This latter eventually helped middle-class men to emulate the manners of the aristocratic class, who had run the country before them. To do so, they provided them with a set of rules of behavior which allowed them to take on their increasingly influential role in society (Berberich).

Despite this preoccupation with the gentleman in earlier centuries, it was only in the 1800s that the appellation of gentleman took on its special significance (McLaren).

John E. Mason explains this shift: « the Victorians inherited the idea of the Gentleman. They added to it, they developed it: they set up factories for gentlemen in their public schools. » (quoted by Berberich 18).

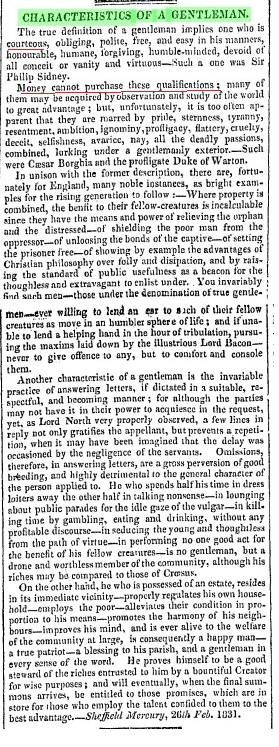

CHARACTERISTICS OF A GENTLEMAN The Derby Mercury -Derby England – Wednesday March 16 1831 Issue 5149.

This column lists a number of qualities and etiquette rules in an attempt to define and clarify the gentlemanly behavior in Early Victorian England. What sticks out is a moral and chivalrous ideal that cannot be purchased by wealth even though the writer underscores that a combination with property could be advantageous to help the needy people.

[THE NEW 19TH CENTURY GENTLEMAN : A TWO-PHASE EVOLUTION]

– The Family Evangelical Gentleman (Early Victorian Period)

The first decades of the 19th century were dominated by the austere, deeply religious gentleman, primarily a family man, under the influence of the “Evangelical reform”.

The Evangelists aimed at improving society corrupted by the excess of the aristocracy during the Regency (roughly 1795 to 1837, characterised by the freedom and extravagance of George IV and a world of glamorous elegance and follies) and the “hell raisers” of “the Grand Tour”, the club society in London and the scandalous behaviour of “Restoration Rakes”. The evangelical reformers prized sincerity and earnestness (i.e seriousness) and stressed the importance of morality, particularly chastity, piety, and charity for others.

On the other hand vanity, frivolity, and foppishness were condemned.

They called for austerity and severity in behaviour, claiming that a « sincere appearance was, like conduct, defined most importantly as a visible manifestation of a well-ordered, morally consistent inner self. » Mangan and Walvin summarized this Early Victorian manliness as driven by “a concern with a successful transition from Christian immaturity, demonstrated by earnestness, selflessness and integrity” (quoted by Berberich 22).

First Rugby Match Between Eton and Harrow (1860 – 1920).

First Rugby Match Between Eton and Harrow (1860 – 1920).

Source: Underwood & Underwood (Photographer). The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection. From The New York Public Library Digital Collections

With the rise of natural science and especially biology, the development of muscle was newly emphasized as « to educate one’s mind one had to educate one’s body« .

Thus, the fascination with health led to a sports and game playing obsession, primarily reflected in public schools for boys. The athlete was the new hero of society.

Boys were encouraged to play sports and abandon childish or effeminate subjects (such as humanities). Football, cricket, and crew once barely tolerated became organized and compulsory. It was believed those activities bred manliness, virility, and respect for duty, the qualities required to reinvigorate the Anglican Church and manage the British Empire (Nagler).

Victorian Muscular Christianity uses then sport to develop Christian morality, physical fitness, and “manly” character.

The Muscular Christian Gentleman & Chivalry Revival (Mid-Victorian Period)

In the second half of the 19th century, after decades of home education, boys were now increasingly sent to the newly formed or reformed public schools. In Eton, Rugby, Harrow, among the most prestigious ones, boys learnt above all else to be men: to grow muscles (by playing rugby and soccer) and to fight for their rightful place. This promotion of sport, classical education, religion and discipline introduced the concept of Muscular Christianity. It stood for neo-Spartan virility as exemplified by stoicism, hardiness and endurance – qualities instilled in the famous aforementioned public schools (Mangan and Walvin). Manliness came to embody “physical and moral courage and strength and vigorous maturity » (Norman Vance quoted by Berberich 21). Tosh connects this adherence to a manly code as an expression of masculinity: « Men must live by a code which affirms their masculinity”.

This code was not unlike that of chivalry that was increasingly revived since the late eighteenth century (from Burke to Richard Hurd). As a matter of fact, Burke equated the principle of chivalry and civilized manners with “the spirit of a gentleman and the spirit of religion” (in Reflections on the Revolution in France, 1790). In The Broad Stone of Honour, or Rules for the Gentlemen of England (1822), Kenelm Digby advocated for instance a « chivalric training » to educate young gentlemen, advising bodily exertion and hardship as a remedy against “effeminate delicacy and the love of luxurious ease” (associated with the previous ideal of politeness). Mark Girouard regards him as having “brought chivalry up to date, as a code of behaviour for all men.” In the early nineteenth century, educationist William Barrow followed this line in Essay on Education. He believed that “hardy and even dangerous diversions” would provide “the rising generation » with « activity of body and vigour of mind (…) and courage and confidence in themselves and their own powers.”

The chivalric system of education also took center stage in the histories of chivalry of the 1820s, such as Mills’s History of Chivalry, or Knighthood and its times (Cohen 324-25). The chivalric system was thus a way of shaping men through martial exercises, habits of fatigue and enterprize. This warlike spirit was expected to bring about a series of civilizing virtues and qualities encompassing affability, courtesy, generosity, veracity, manliness, bravery, loyalty, purity, honor, and a strong sense of protection toward the weak and oppressed (Cohen 326).

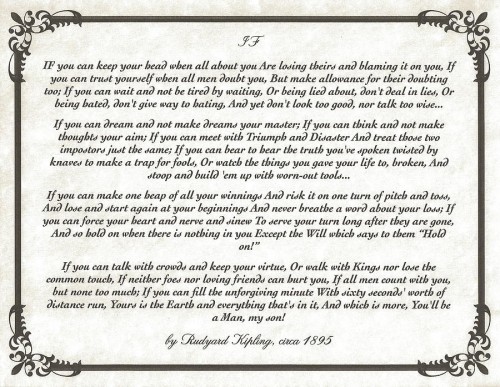

In his famous poem If Rudyard Kipling typifies this masculine ethos by celebrating British stoicism and masculine rectitude, that is the classic British « stiff upper lip » as he came to be dubbed. In other words a strong and self-reliant man in control of his emotions (self-control).

The stress was no longer on educating refined gentlemen and etiquette books, but on raising hardened empire-builders, and tough adventurers ready to conquer new worlds !

Nonetheless, the Victorian gentleman was still a Romantic at heart, deeply embedded in rose-tinted medieval notions of chivalry and kinght-errantry. Girouard points out that the goal of the revival of the chivalry tradition was to produce a ruling class self-justified by its moral qualities worth of rulers. Therefore, gentlemen were to run the country because they were « morally superior. » The public schools then institutionalized this new ideal with service to the nation as a long-term goal.

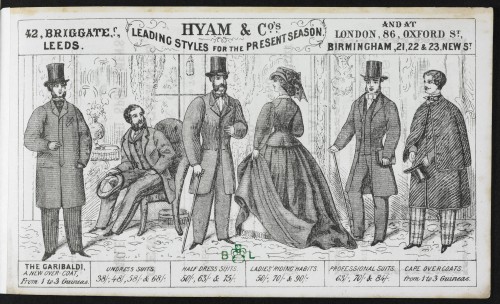

Advertisements such as this, for Hyam & Co (1870s), used images of men that promoted the idea of a respectable Victorian gentleman. It showcases the ‘leading styles for the present season’ for men and boys. Its production of suits for ‘Eton, Harrow & Rugby’ reveals the high status of this brand.

Hyam and Company was a successful Victorian clothing manufacturer and outfitters with a chain of shops in London, Birmingham and Leeds.

The Rise of the Middle Class and the Self-Made Gentleman

Another important factor brought about by the Victorian period and the industrialization regarding the definition of the gentleman lies in the growth of a wealthy middle-class (despite the rampant poverty of the working class). In their quest for social esteem and prestige, in a society still dominated by the land-owning aristocracy, the “rank” of gentleman proved to be very attractive to them as the “ultimate benchmark. » Unlike most of Europe at the time, they did not feel any aspiration to overthrow the old order even though they were eager to establish their own cultural identity.

« Refinement » and « intelligence » became key to signify not necessarily a distinction of blood but a distinction of position, education and manners (Berberich). Character, courtesy, and cultivation were declared to be replacing birth and wealth (which remains however important in terms of lifestyle) as the hallmarks of the « natural gentleman » (Angus).

Hence the formation of two kinds of gentlemen: the man of noble birth or good family, who was a gentleman by right, and the self-made gentleman (or « nature’s gentleman »).

This distinction came to be dubbed the « gentleman of birth » as opposed to the « gentleman of worth ». Mason (16) points it out as well and stated that the latter was devoid of class connotations: everyman could aspire to it, provided he adhered to the set code of manners advocating honor, charity and social responsibility.

Thus, despite the pressures of an increasingly competitive and capitalistic world, the gentlemanly ethic as a bonding credo for men, fosters certain ideals of honesty and generosity (Angus).

« The Cornhill Magazine » (1860-1975) was a Victorian magazine and literary journal in London. It included a selection of articles on diverse subjects and serialisations of new novels. It hoped to compete with « All the Year Round », a similar magazine owned by Charles Dickens, and he employed as editor William Thackeray, Dickens’ great literary rival at the time.

« The Cornhill Magazine » (1860-1975) was a Victorian magazine and literary journal in London. It included a selection of articles on diverse subjects and serialisations of new novels. It hoped to compete with « All the Year Round », a similar magazine owned by Charles Dickens, and he employed as editor William Thackeray, Dickens’ great literary rival at the time.

In the Cornhill Magazine, Fitzjames Stephen stresses the importance of the moral component in the status of gentleman which « implies the combination of a certain degree of social rank with a certain amount of the qualities (…); but there is a constantly increasing disposition to insist more upon the moral and less upon the social element of the word » (my emphasis).

Gentleman vs. Dandy and the Decadence of the Gentleman

The dual nature of gentlemanliness led to a constant debate and redefinition. One of the problems the Victorians faced was to preserve its exclusiveness while making it more inclusive.

Moreover, under the influence of the figure of the dandy (sort of evil twin of the gentleman, who advocated idleness and uselessness), the gentleman should be able to live without working (and free from « base » business preoccupation) so that he could dedicate himself to leisure and the cultivation of style in accordance with gentlemanly life. This view clashed with the idea that it was out of the gentleman’s character to live off other people’s toil (Gilmour, p.7) but also economic ambition, thrift (like « Scrooge » minus his stone-hearted character) and responsibility (running into debt was shameful). Thus, it challenged the dignity of (hard) work and thereby undermined the building blocks of the new industrial society. The letter from The Complete English Tradesman by Daniel Defoe written in 1726 exemplifies well this ideological dispute.

« The Importance of Being Earnest – Cigarettecase » – Photograph taken at St. James’s Theatre, London 1895. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Oscar Wilde contributed of course famously to the figure of the « gentleman-dandy », prominent in his comedies of manners. He used him both to poke fun at the hypocrisy and superficiality of the upper class along with its strict code of morals through his hilarious cynicism, but also to call for a life motivated primarily by pleasure, as contended by Jack in The Importance of Being Earnest: « Oh, pleasure, pleasure! What else should bring one anywhere?« , while Algernon mocks especially the -boring- institution of marriage, one of the tenets of the family gentleman. Miss Prism unites these two themes by commenting -reproachfully- that « people who live entirely for pleasure usually are [unmarried], echoed by her niece Cecily who praises « one who leaves the pleasures of London to sit by a bed of pain.« . These two views represent the straitlaced Victorian society in opposition to self-indulgence. Wilde’s voice can be heard in Algernon’s statement/plea that his « duty as a gentleman has never interfered with [his] pleasures (…)« , that can be read as an attempt to show that the two were not incompatible contrary to the common belief and that having a good time was not immoral. Ultimately he echoes the author’s dandy philosophy that living should be a kind of art in which one creates oneself, fashioning themselves as art with refines tastes and values (dandy-aesthete). An elite class who stood beyond the dictates of everyday life and also allowed to transgress it if they desired it (same-sex intimacy or womanizers)(Losey).

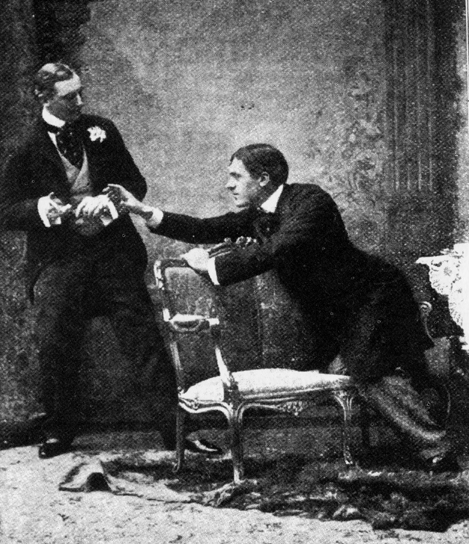

Finally the late 19th -fin de siecle- scandals associated with the rise of criminality (cf: « Jack the Ripper »), prostitution (including children) and homosexuality observed in « seemingly perfectly respectable Victorian gentlemen » also tarnished and threatened this ideal by revealing his hypocritical facade and degeneration. The gentleman turned to be a « scoundrel » (Dryden). This is embodied in the character of Dr Jekyll (representing the quintessential bourgeois gentleman, an affluent and educated member of an established profession) and Mr Hyde who symbolizes the -repressed- dark side of the gentleman in complete contradiction to his moral standards and decency… We find also this duplicity, in a more lighthearted way, in the character of Jack by Oscar Wilde who lives a double life (upstanding in the countryside and hedonistic in London under the fake name of « Ernest », which serves also to satirize the « earnestness » of the traditional gentleman). « The revelation of corruption and abuse on the part of « respectable gentleman, (…) shook English moral complacency to its foundations« , comments Dryden (64).

The Norton Anthology (1030) points out Sherlock Holmes, the hugely popular « gentleman detective », created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in 1887, both « embodies and polices London’s cosmopolitan decadence« , a city which is likened to « a great cesspool into which all the loungers and idlers of the Empire are irresistibly drained » according to his sidekick Dr Watson. [Alexandra Galakof, Academic Paper – MA in English Literature at La Sorbonne Nouvelle in Paris]

– I will be glad if you liked to cite this paper :-), you can reference it as below (MLA format) :

Galakof, Alexandra. « The Figure of the Gentleman in 19th century Victorian England : The re-Fashioning of a Manhood Ideal. » Buzz littéraire: Littera, 21 July 2015, buzz-litteraire.com/the-gentleman-figure-in-19th-century-victorian-england-the-re-fashioning-of-a-manhood-ideal. Accessed XX

« Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde poster » by Chicago : National Prtg. & Engr. Co.Modifications by Papa Lima Whiskey.

(1880S)

See also on a related topic:

Gentleman vs. Tradesman according to Daniel Defoe (textual analysis of « The Complete English Tradesman », Letter XXII, The Complete English Tradesman, 1726, Of the Dignity of Trade in England more than in Other Countries

The Creation of the Man of Feeling : Age of Sensibility and Romanticism in 18th century England

——————–

WORKS CITED:

Berberich, Christine. The Image of the English Gentleman in Twentieth-Century Literature. Routledge, 2007.

Cody, David. « The Gentleman. » Victorianweb.org. Web.12 April 2015

Cohen, Michèle. »‘Manners’ Make the Man: Politeness, Chivalry, and the Construction of Masculinity, 1750–1830. » Journal of British Studies, 2005, pp. 312-329.

Corfield, J.Penelope. « The Rivals: Landed and Other Gentlemen, » Land and Society in Britain, 1700-1914. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1996.

Dryden, Linda. The Modern Gothic and Literary Doubles: Stevenson, Wilde and Wells. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

Girouard, Mark. The return to Camelot: Chivalry and the English Gentleman. Yale University Press, 1981.

Greenblatt, Stephen. Introduction “The Victorian Age”. The Norton Anthology of British Literature, Volumes E, 9th edition. Ed. New York: Norton, 2012.

Mangan, J. A., and James Walvin. Manliness and Morality: Middle-Class Masculinity in Britain and America, 1800-1940. Palgrave Macmillan, 1987. (quoted by Dr Christine

Gilmour, Robin. The Idea of the Gentleman in the Victorian Novel. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1981.)

Losey, Jay, and William Dean Brewe. Mapping Male Sexuality: 19th Century England. New York: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2000. Print

Mason, Philip. The English Gentleman: The Rise and Fall of an Ideal. William Morrow & Co, 1982.

McLaren, Angus. The Trials of Masculinity: Policing Sexual Boundaries, 1870-1930. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 1997.

Nagler John. « Muscular Christianity in Levick’s Rugby Football. » Victorianweb, http://www.victorianweb.org/sculpture/levick/nagler.html. Accessed 12 April 2015

Vance, Norman. The Sinews of the Spirit: The Ideal of Christian Manliness in Victorian Literature and Religious Thought. Cambridge University Press, 1985.

——————–

[RESEARCH PROCESS AND PERSONAL INTEREST]

In keeping with my precedent romantic digital project dealing with the refashioning of the masculine identity during the Age of sensibility, I was interested in pursuing my exploration in the Victorian period, a high point in the shaping (and bolstering) of gender roles.

I was primarily interested in the figure of the Dandy as a big fan of Oscar Wilde but for some reason I did not manage to find books about it, so I decided to investigate his « twin brother », the gentleman who represents his more positive side.

I realized that my preconceived ideas that a gentleman was essentially about fashion and good social manners were partially false. Indeed, his character was, especially during the early Victorian period, re-fashioned in reaction against 18th century aristocrats’ vanity and frivolity, focusing too much attention on appearance and clothes, « [wearing] a fine attire but rotten to the core« . Hence a return to more spirituality, rectitude and morality as tenets of the Victorian honor code.

Still, the definition is not necessarily clear and remains a matter for debate. Underlying this argument, lies an ideological struggle/antagonism of social classes, and conflicting beliefs between the traditional aristocracy, and the new bourgeois middle class in search of a more democratic society (favoring merit over birth).

This time I did not have any difficulties to pull up some primary sources, running simply the key word « gentleman » which was pervasive in the press and the literature of the time.

Derniers commentaires